The heat is on: Carbon capture with benefits

Turning CO2 into plastics, fuels and other essentials offers a bold new way to fight climate change while meeting the world’s growing demands.

Plastics are everywhere, from the bottle of water in your refrigerator to outdoor furniture, food packaging, toys and even waterpipes. At the heart of these everyday items are compounds called olefins—typically derived from fossil fuels—prized for their stability, low density and cost-effectiveness.

The growing demand for these chemicals creates hurdles for governments. Nations are trying to urgently reduce carbon dioxide emissions, amid predictions that global plastic use will spike from 464 million metric tons in 2020 to 884 million metric tons by 2050.

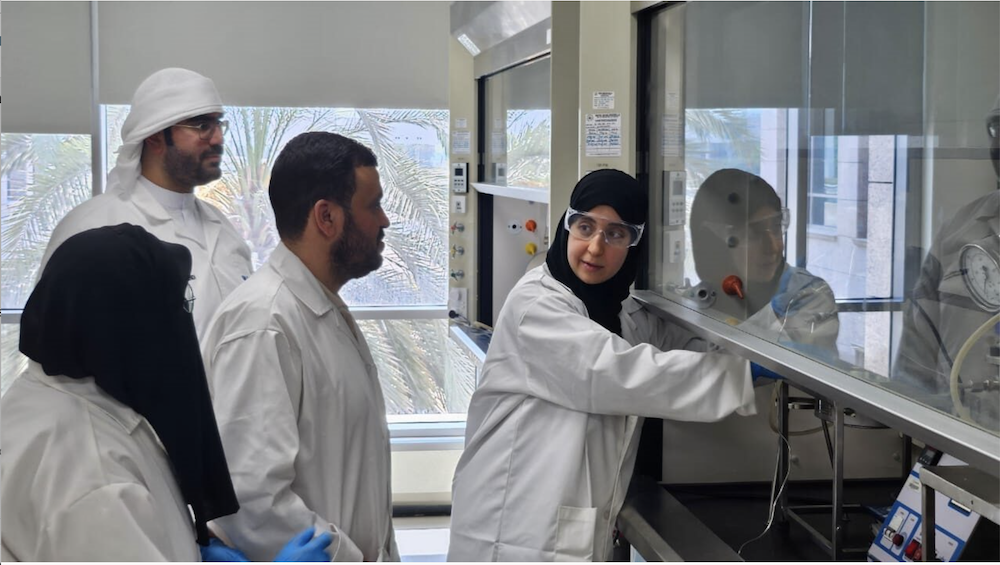

To tackle both problems at once, Maryam Khaleel’s lab at Khalifa University is developing catalysts that can convert carbon dioxide into a variety of different products, including olefins. This keeps carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere while helping to meet the rising demand for industrial feedstocks.

“The catalyst reactions are not 100% controllable, but we’re moving in the right direction.”

Maryam Khaleel

The work is part of the university’s work to tackle national challenges from the ground up; investing in the talent, resources and time it takes to develop new technologies; even if it may take years before they can be commercialized.

As global carbon emissions continue to rise, finding a range of solutions is essential, Khaleel says. “We have a potential way of getting useful products out of this problematic gas contributing to global warming,” she explains. “It can’t be the only way to solve the problem, but it’s one way of getting something beneficial instead of just sequestering carbon dioxide underground.”

Producing sustainable building blocks

Khaleel’s lab is exploring ways to turn CO2 into several products, including methanol, a potential fuel. But one of the most important research areas is transforming CO2 into olefins in a single step using a single catalyst. Olefins are the building blocks for polyethylene and polypropylene, two of the most widely used plastics.

“Converting CO2 into olefins is in high demand,” says Sadiya Mushtaq, a PhD student in Khaleel’s lab who works on producing ethylene, propylene and butylene, which are used to make everything from plastic bottles to paints and cosmetics.

The team is working to develop catalysts that can facilitate the CO2-to-olefins conversion. “A catalyst is a material that basically speeds up the reaction and reduces the energy consumption needed for the reaction to proceed,” Khaleel says. “We’re not quite at the point of having our catalytic materials used on a larger scale, but we have developed catalytic materials that have a decent CO2 conversion, above the 40% that is the average in the existing scientific literature.”

The team is focusing on developing a tandem catalyst. This involves combining two catalysts inside a reactor to produce olefins. While the conversion rate is improving, controlling which products are made has been particularly challenging.

“The catalyst not only forms desired products, olefins, it comes with a cost of [producing] many other undesired byproducts,” Mushtaq says. In some experiments, only 20% are olefins; the rest are byproducts such as methane, ethane and paraffins. “That’s one of the biggest challenges in these reactions.”

The ideal scenario—a reaction with only the desired products—is more energy efficient. “You don’t need to separate anything downstream; you just have your product that you can immediately use with high purity,” which is another requirement for polymer synthesis, Khaleel explains.

“The catalyst reactions are not 100% controllable, but we’re moving in the right direction,” she says. “Ultimately the goal is to prepare a catalyst material that can convert carbon dioxide 100% into whatever product we want.” Khaleel estimates that the technology is likely about a decade away from being ready to market.

PhD student Abdulla Alhendi is working to create a different product: gasoline. “People are capturing CO2 to rectify its environmental impact, but there haven’t been many beneficial applications to use it for,” he points out. “We want to convert CO2 into gasoline, which will provide us with a carbon-neutral fuel.” The CO2 conversion technology for gasoline and olefins requires further research and refinement to meet the standards required for commercial application, he adds.

Supportive environments

Converting CO2 to olefins, gasoline and other products is not without risk. Running the chemical reaction inside the reactor requires temperatures of up to 450°C and high pressures of 30 to 40 bar. For comparison, atmospheric pressure on earth is around one bar.

“Operating a reactor at 30 bar introduces safety hazards to a human working space, so we try to ensure everything is safe before starting the reaction,” Mushtaq explains. The day before an experiment, the researchers run a series of tests to detect potential gas leaks and make sure gas detectors and other safety equipment are working.

Before conducting her first experiment, she was extremely worried about the risk involved. “I was literally shivering the first time I did a reaction going beyond 10 bar, because it’s such a high-pressure reaction,” she recalls. But Khaleel worked alongside her for a month and helped put her at ease. “Without her, I don’t think I would have the confidence to come to the lab alone and do the reaction.”

As a PhD student or postdoc, selecting a university and an advisor that are supportive is key, Mushtaq adds. “It’s not just about the project, it’s about your advisor as well; how much she understands you and how she tackles problems and guides you,” she says. “This university and the people here welcomed me with an open heart. And the research going on here is top notch.”