Cell by cell: Tackling aging from the inside out

Targeting aging at the cellular and genetic level promises a new approach to healthy, long lives.

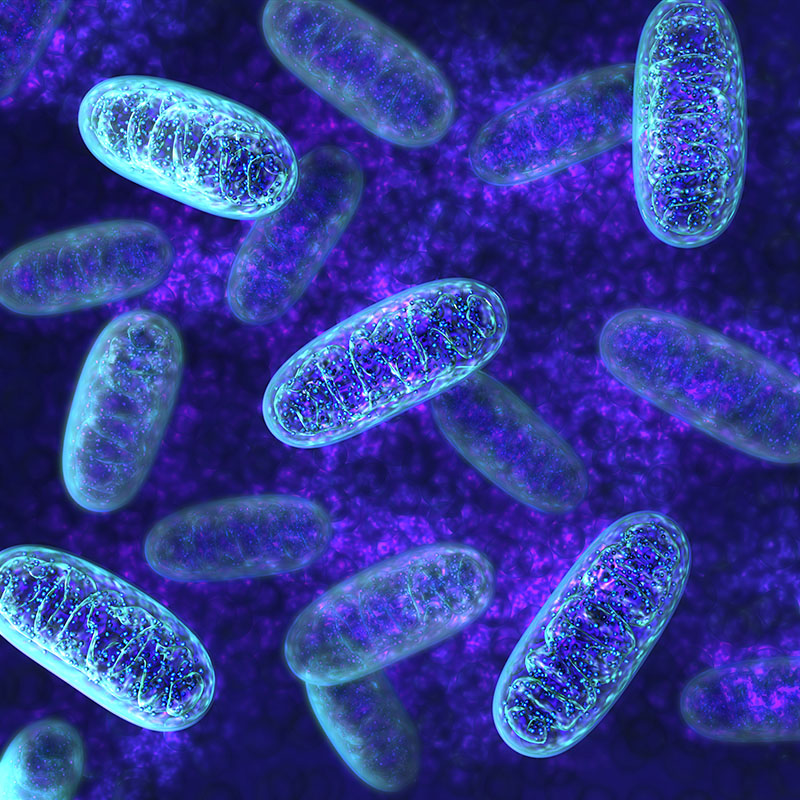

Mitochondria, those tiny organelles that supply your cells with energy, might hold the key to keeping fit, active and disease-free far into old age.

Most aging research has focused on the accumulation of mutations in genes carried in the genome of the cell nucleus. But a new study in mice has shown that the tiny mitochondrial genome also accumulates genetic damage over a lifetime, and this varies between individuals1.

When mitochondria malfunction, their ability to produce energy declines, and they are more likely to leak electrons, generating free radicals that damage surrounding cells. So, mitochondrial genetic differences can also influence the animals’ health and lifespan, says Saleh Ibrahim, from the College of Medicine and Health Sciences, who led KU’s contribution to the research. The team is now investigating treatments to support healthy long-term mitochondrial function.

The mitochondria project is part of a broad KU contribution to UAE’s healthy longevity initiative, a national effort to improve health and wellbeing into old age by counteracting cellular mechanisms of aging.

“What we experience as aging is the cumulative activation of specific biomolecular pathways that lead to dysfunction at the level of cells, tissues, and eventually, the whole body,” Ibrahim says. It’s that thinking that has led KU researchers to focus on a range of cellular mechanisms, including those related to bone loss, reproductive healthspan and diabetes, as well as mitochondrial genetic damage.

“This may or may not increase human lifespan—although evidence from animals suggests it could be possible,” Ibrahim says. “But at least we can extend the healthspan—the years of life spent healthy and active.”

“We are comparing unusually long-lived mice with those that have normal lifespans, analyzing the biochemical pathways affected.”

Saleh Ibrahim

Ibrahim’s focus is the mitochondria, which carry their own tiny genome inherited from a mother. His team has shown that the complex interaction between a person’s mitochondrial genome and the nuclear genome—inherited from both parents—can also influence healthy aging.

To further explore this, Ibrahim developed mice with identical nuclear genomes, but different mitochondrial genomes. Working with researchers from the University of California, Berkeley, in the United States, they confirmed that the rate of mitochondrial mutations depended on which variant of mitochondrial genome they carried rather than depending solely on the nuclear genome.1

“The finding confirms that we should target this pathway to increase healthspan,” Ibrahim says. “We are comparing unusually long-lived mice with those that have normal lifespans, analyzing the biochemical pathways affected—from which we can test natural compounds known to target those pathways,” he says.

The UAE is the ideal country for conducting healthy aging research, Ibrahim says. “There is a forward-thinking government here, and a lot of investment.” Other KU projects contributing to UAE’s health longevity initiative include Habiba Alsafar’s work on the Emirati Genome Program—a reference genome of the local Emirati population that will underpin research into cellular aging mechanisms. Alsafar has already identified a gene strongly associated among Emirati with type 2 diabetes2, a major public health challenge for UAE.

KU researcher Ayman Al Hendy is also targeting a locally prevalent health condition, exploring stem cell derived treatments to extend male and female reproductive healthspan. “This approach could treat a form of female infertility called premature ovarian insufficiency,” Ibrahim says.

Joining KU’s growing effort to support healthspan is Moustapha Kassem, a recent recruit studying the cellular pathways underlying age-related bone loss. “Our work has identified several novel regulators of bone formation that contribute to age-related bone loss,” Kassem says.

In the lab, Kassem has shown that senolytics—compounds that selectively kill dysfunctional, aged ‘senescent’ cells—could benefit bone health in older people. “We are now [moving] into human clinical trials, including testing the use of senolytics to improve musculoskeletal health in elderly individuals,” Kassem says.

Kassem’s recruitment broadens KU’s growing strength in aging research. “KU offers a state-of-the-art platform for high-quality cellular and molecular work and is pioneering experimental clinical trials on aging interventions in Abu Dhabi,” Kassem says.

References

- Serrano, I. M. et al. Mitochondrial somatic mutation and selection throughout ageing. Nature Ecol. Evol. 8, 1021–1034, 2024. | Article

- Al Safar, H. et al. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms among Emirati patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Steroid Biochem. Mole. Biol. 175, 119-124, 2018. | Article