Building an autonomous future

Researchers are building world-class robots at Khalifa University’s Center for Autonomous Robot Systems.

Ten years ago, when Ruqayya Alhammadi was 16, she attended a celebration for gifted students at Khalifa University. She returned home with a LEGO robot kit to build and program her own robots. Today, Alhammadi is contributing to the development of a lunar rover that the United Arab Emirates may one day send to the moon.

The work is part of her PhD project at the Khalifa University Center for Autonomous Robot Systems (KUCARS) where investigations range from smart medical devices and underwater robots to automated greenhouses, autonomous vehicles, and even robotic birds used to help preserve endangered species.

With a dynamic cross-disciplinary team of around 12 faculty, about twice as many postdoctoral fellows, and 40 graduate students, KUCARS has become a hub for early-career researchers, providing them with a thriving environment to pursue diverse and ambitious robotics research projects.

This transformation contrasts with KUCARS’s early days, when its founder Lakmal Seneviratne was invited in 2010 to set up a robotics research center at the then-newly established Khalifa University.

Designing a top-tier robotics program from scratch

At the time, Seneviratne was finishing his term as Head of School of Engineering at King’s College London, where he was also the founding Director of the Center for Robotics Research. “When you are a faculty member at a university like KCL, you have very little incentive to move,” he says.

Ultimately, Seneviratne chose to come to Khalifa University for the challenge of working in a new university in a new culture. “It was small but very dynamic and people had the vision and resources to do things. I never thought I would stay this long,” he says.

For Seneviratne, it was an opportunity to create a top-tier research center focusing on autonomous robotics, a fast-evolving field that combines robotics with artificial intelligence and advanced sensing.

The university provided the funds to excel, offering not only standard laboratory equipment, but also specialized facilities. These include a state-of-the-art marine robotics pool that simulates ocean waves, automated greenhouses, and an autonomous car lab.

The center employs research staff to support its investigators who do everything from 3D print robot parts to help integrate electromechanical systems. “This way, we do not have to start our experiments from scratch,” Alhammadi says.

KUCARS also provides other opportunities for researchers and students alike. For example, it will host the 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), one of the largest and most important global meetings on autonomous robots. It also created and hosted the prestigious Mohammed Bin Zayed International Robotics Challenge (MBZIRC) in 2017 and 2020.

Seneviratne has been working on attracting a diverse team of researchers to KUCARS. He first recruited collaborators, including Jorge Dias and Yahya Zweiri, a King’s College colleague. He also reached out to young scholars, such as Federico Renda and Irfan Hussain, faculty of mechanical engineering.

“There were lots of new things and technology adoption happening here and I felt there would be many places where I could contribute.”

Irfan Hussain

“Extra fingers”

Growing up in Pakistan, Hussain realized that engineering would offer him a wider range of experiences than his other dream, medicine. Originally drawn to mechatronics, which combined mechanics and electronics, he moved into robotic systems while pursuing his PhD in information engineering from the University of Sienna, Italy.

Hussain joined KUCARS as a postdoc, then accepted a faculty position despite other offers from three prestigious European research centers. “I thought I had enough exposure to Europe. There were lots of new things and technology adoption happening here and I felt there would be many places where I could contribute,” he says.

At first Hussain continued the work he began in Sienna on extra fingers to help stroke patients grasp objects. Stroke often affects only one side of the body and after rehabilitation, many patients have one functional limb but can no longer use their other hand. To overcome this problem, he developed a wristband with a six-jointed robotic limb or ‘sixth finger’ which coils around objects, locking them into place against the unfeeling hand, allowing patients to use their good hand for tasks requiring more dexterity.

Working with Chalmers University, in Sweden, Hussain developed a user-friendly control system consisting of a cap with sensors that picks up electrical signals from muscles in the forehead. “If a patient flexes those muscles once, the finger closes,” Hussain explains, “Flex it twice and it opens. It takes only five minutes for them to start using it.” Italian company Existo is in the process of commercializing the technology.

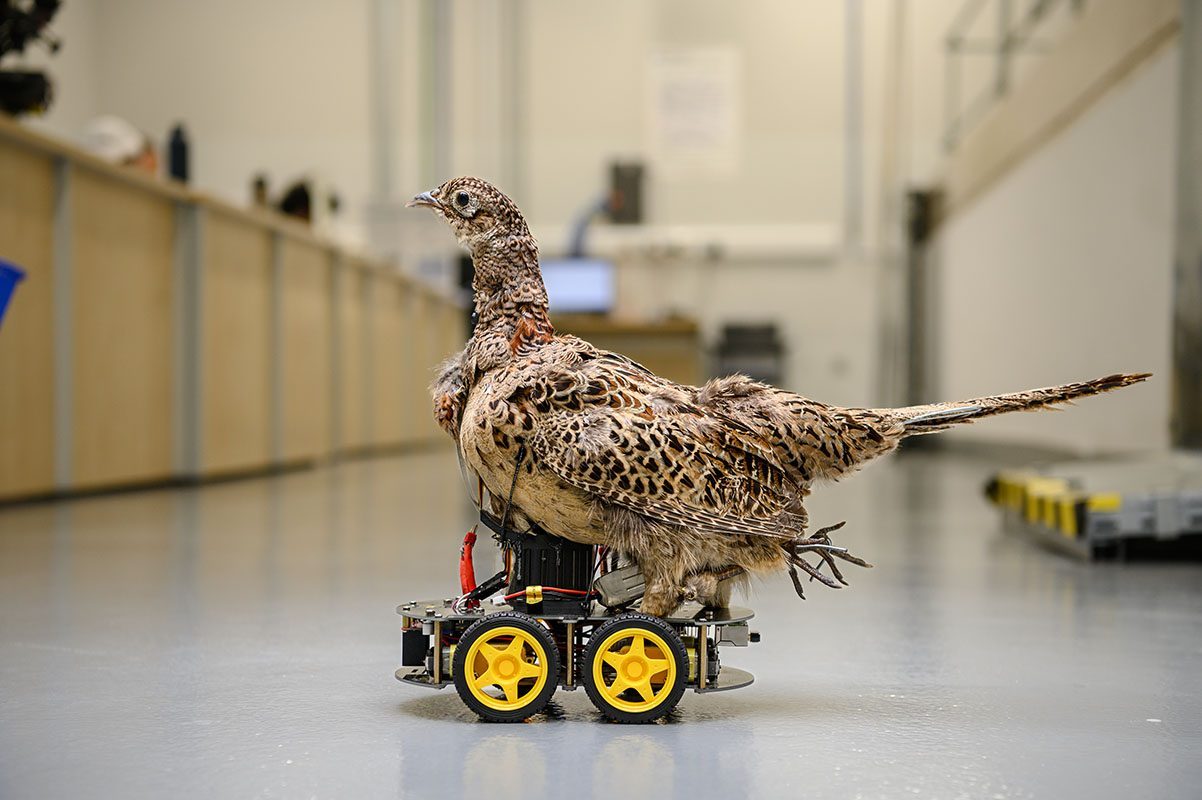

Hussain is also working on a robotic bird to mimic the local houbara bustard, which is endangered due to hunting and habitat destruction. The robot can unobtrusively monitor the birds and then move in ways that spark mating behavior in males. Researchers hope the robot will capture sperm from wild houbaras to improve the diversity of the captive breeding stock.

Navigating underwater environments

Hussain and several other early-career KUCARS researchers are also working on underwater robots. Murky water interferes with the robot’s imaging, communications, and pinpointing its location. Waves make it harder to perform common tasks, such as grasping or tying the ends of two ropes together. To investigate this environment, the university has invested in a 10 x 17.5 x 4-meter marine robotics lab at KUCARS, equipped with piston-mounted plates to create waves reproducibly so engineers can precisely measure how their robots respond to them.

Khalifa University has invested in a marine robotics lab at KUCARS, equipped with piston-mounted plates to create waves reproducibly so engineers can precisely measure how their robots respond to them.

One ongoing project involves fish farming, where nets are used to confine and then harvest fish. Nets are prone to biofouling, increasing their weight until they rip. Human divers are used to inspect and repair nets, as well as monitoring fish health, to keep aquaculture facilities operating properly. It could potentially be more efficient and cost-effective and for robots to inspect fish, as they could spend more time underwater, Hussain says. Unfortunately, training AI to identify problems under low-light conditions amid the constant movement of the fish is extraordinarily difficult. He uses the wave pool to simulate fish and nets and gather the data needed to train AI vision systems to make sense of what they see. Ultimately, Hussain also hopes to teach his robots to repair torn nets.

Maryam AlShehhi, an assistant professor who spent two years as a postdoc at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) before returning to Khalifa University, works with KUCARS to monitor coral reefs robotically. Coral reefs, vital ecosystems at the bottom of the food chain, have faced imbalances due to climate change. Robots would enable AlShehhi to monitor coral more frequently at levels down to 300 meters to better understand those changes, potentially facilitating the transplantation of the healthiest coral to new locations. Through KUCARS, she is collaborating with Stanford University, which has developed an underwater humanoid robot that was recently demonstrated in the KUCARS marine robotics Lab.

Building for the future

Meanwhile, Alhammadi is working to keep her lunar rover from slipping. This happens when its wheels cannot grip the soil and just spin without moving. Slipping previously trapped the golf-cart-sized Mars Spirit rover and delayed the mission of its twin, Opportunity, by several weeks.

Alhammadi’s solution to this challenge involves building a vision system that classifies lunar and Martian soils, allowing the rover to make real-time adjustments. To better predict rover performance, Alhammadi has built a lunar test bed filled with ultrafine sand so she can run realistic tests. Her goal is to change rover operational variables such as lighting, inclination and compaction, and use the data she collects to train the robot to make better decisions about its path.

Like other early career researchers at KUCARS, Alhammadi is delighted with the support she has received working in a cross-disciplinary team. After finishing her PhD, she plans to take a two-year postdoc overseas, before returning to KUCARS, where robots are moving from a teenager’s dreams into the mainstream.

Khalifa University has invested in marine robotics lab at KUCARS, equipped with piston-mounted plates to create waves reproducibly so engineers can precisely measure how their robots respond to them. KUCARS researchers have developed a wristband with a six-jointed robotic limb or ‘sixth finger’ which coils around objects, locking them into place against the unfeeling hand, allowing patients to use their good hand for tasks requiring more dexterity